EX ORIENTE LUX:

A BYZANTINE ROAD TRIP THROUGH

ITALY

Italian road trips summon visions of putti whirling around gilded oil-paintings, endless feasts paired with bottles of Sangiovese and glamorous models sustained by nutty espressos or worse.

Even those allergic to sanitised caricatures tend to conjure truffle hunts in Tuscany or bouts of bear-watching in Abruzzo; the glistening waters of Campania or the glacial lakes of the north.

No matter how enlightened, what rarely leaps to mind are the Byzantine pearls of the peninsula. Despite Italy possessing massed ranks of Byzantine saints, fragile icons and mercurial mosaics, the Eastern Roman Empire has somehow been reduced to a spectral presence; as if its mongrel Hellenism, Romanitas and Semitic iconography were just an embarrassingly conservative prelude to the liberty and realism of the promethean Renaissance.

So, let’s vandalise the gothic baubles, smash the baroque idols and daub the blanched statuary in Byzantium’s bright spectrum. It’s time to uncover the country’s Byzantine underbelly in twelve days in the hope of extricating the golden-stranded DNA of its civilisation from the tired corpse of Italian travel clichés.

This is not an exhaustive guide; such a task would require a book. There are plenty of Byzantine marvels omitted here for the sake of a convenient road-trip, not least Pavia’s San Pietro in Ciel d’Oro, for instance, with its twelfth-century apse and tombs of Augustine and Boethius. And there are also churches (like Santi Quattro Coronati and San Vitale) that, despite being Byzantine structures, lack apse decoration that dates to the era.

DAYS I-II: SICILY

The land of Cyclops suffers a poor reputation as a third-world Italy, full of migrants, rubbish and illegal developments. When viewed positively, it’s the mainland on steroids, home to nostalgic Godfather (1972) scenes or The Leopard (1963). Backhanded compliments like “vibrant” get chucked around. But mostly it’s seen as a dysfunctional extension of the Cosa Nostra; the sort of place even mediocrities like Roberto Vecchioni feel able to call “Isola di merda.”

It’s true, as one of the most deprived regions in the country, Sicily can sometimes feel as though potholes outnumber cars and council blocks exceed villas (with monuments that make mock concessions to local culture). However, to focus on these cauterised boulevards is to ignore the space and greenery of its innards, beaches like San Vito lo Capo or the priceless patter of locals.

Using Taormina (home to one of the main Byzantine fortresses on the island) as a base, there’s really only one place to stay: Belmond’s Grand Timeo. Dominating a cliff-face below the third-century BC Greek theatre, the fluorescent vistas that span Etna and the coast are almost a match for the Deluxe suite’s classical whites and blues. Indeed, a shocking six acres of greenery are the hotel’s own. And if that’s still not isolated enough, there’s always the private beach of the hotel’s sister property, Sant’Andrea.

Villa Romana del Casale

Visitors must keep reminding themselves the mosaics are worth it as they make their way into Sicily’s interior (most settlements are along the coasts), especially as they negotiate the gauntlet of souvenir stalls between the museum and car park. Justification is swift, however, as 3,500 square metres of world-class fourth-century mosaics cover the villa cum palace, which include famous scenes such as the bikini girls, little hunt, great hunt and Polyphemus. Most remarkably, the villa is very remote, adding to the haunting tension of a civilisation versus nature backstory.

Villa del Tellaro*

Romana’s lesser known twin-sister, Tellaro, is a two-hour drive south near Noto. Smaller in size and surrounded by vineyards, it was only made accessible to the public in 2008 and so still tends to lurk beneath the typical tourist’s radar. Despite this its relative unpopularity, the mosaics are no more basic in comparison to those at Romana. Instead, though severely damaged, they’re executed in a different style that some claim is North African, and contain fascinating scenes such as the ransom of Hector’s body wreathed in Bacchic vignettes.

Cefalu-Palermo

En route to Palermo, park the car beach-side at Cefalu where Roger II built a Romanesque cathedral beneath a giant spur. An inscrutable Christ Pantokrator looms large in the apse above the Virgin and four archangels. Though the real sixth-century Byzantine mosaics – not this Norman nonsense – depicting birds and foliage are still being excavated.

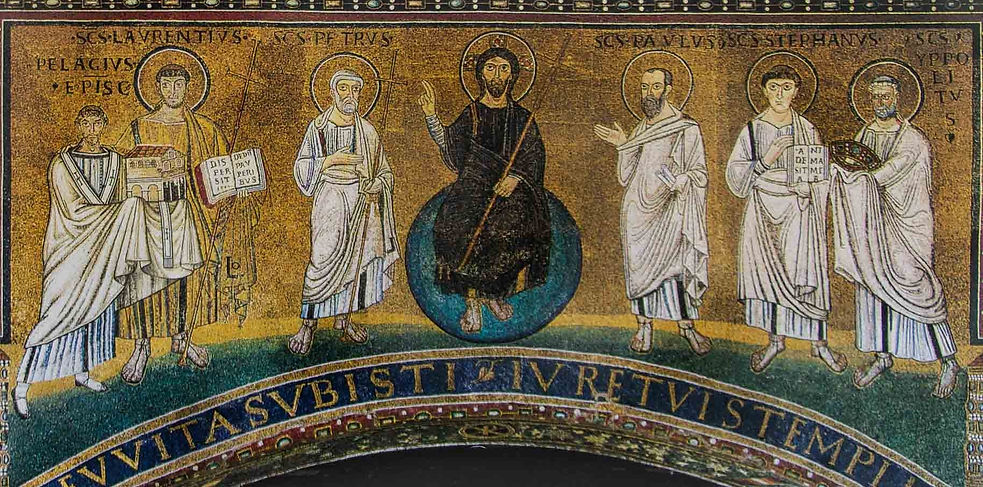

Then proceed to the capital where the Palatine Chapel of Aachen (itself modelled on San Vitale) finds its Sicilian counterpart. Annoyingly, there’s an almost identical pantokrator to the one at Cefalu, but the highlights of this bronze cocoon are more numerous and include the muqarnas ceiling, St John in the desert on the north wall and Jesus seated with Sts Peter and Paul.

A 10-minute walk brings travellers to Martorana: George of Antioch’s church. Spliced with baroque features, it’s the Byzantine elements that shine. Indeed, the gaze fixes less on the unremarkable dome, or Roger (bypassing the Pope and getting crowned by Christ), but rather the mosaic of Mary at the annunciation, which seems drenched in lushness, as well as the cerulean blue of St Anne in the side apse (which is the sort of colour you want to drown in).

Monreale

Let’s be honest, at this point you’ll have mosaic fatigue; it’ll be hard to bear another identikit Norman commission (with scenes lifted from the Byzantine emperor, Basil II’s Menologion). Byzantine craftsmen probably thought the same. So, once at Monreale, you’re really there to see William I’s porphyry sarcophagus – especially as the Byzantine equivalents at the Istanbul Archaeological Museum are in such a poor state – as well as the seraphs of the side-chapel, the ornate capitals, and the cognoverunt eum in fractione panis (they recognised [Jesus] in the breaking of the bread [at Emmaus]) mosaic.

DAY III: CALABRIA

Messina is nothing to look at for the same reason as Reggio Calabria (ancient Rhegium): both were struck by a huge earthquake in 1908. So visitors can afford to ignore both as they ditch the ferry and drive into the deep south, the mountainous Mezzogiorno. This is definitively razzia country now, where Arab raiders took captives and even occupied cities for much of the West’s Dark Ages (sacking the old basilica of St Peter’s in AD 846).

If Como feels more German than Italian, Calabria is its Greek cousin. Once home to the city-states of Magna Graecia (remembered in popular history thanks to the exploits of Pyrrhus of Epirus, who gave us the word “pyrrhic”), there are still isolated hill-communities around where Albanian and Greek are spoken by the descendants of sixteenth-century refugees. Indeed, Calabria’s often overlooked compared to its counterparts in Italy’s boot because it lacks the headlining cities – the Matera or Lecce “the Florence of the South” – of its competition. Perhaps the closest it has is Crotone, roughly half an hour north of Praia Art Resort.

Not that the ignorance has been a bad thing. Instead, it’s formed an aegis. For a long time, Calabria’s Ionian coast has been the country’s best kept secret. And the tiny ten-bedroom Praia has made the most of its enigmatic location, reserving the best spot for itself between the coast and the protected marine reserve of Capo Rizzuto. Furnished by local craftsmen and supplied with ingredients from the pine-pocked hillside, its suites ooze rustic elegance and are only a mangonel’s throw from Valli Cupe’s waterfalls.

Cattolica di Stilo*

En route to Praia from Reggio, there’s a pit-stop from the scourging sun at Stilo where a ninth-century Byzantine church contains frescos that seem strikingly similar to those at Sant Clement de Taull and Santa Maria de Mur in Spain. The observant will notice two curious items inside. The first, an Arabic inscription of the Shahada on one of the columns. The second, an upturned Corinthian capital, which might suggest it was brought from the ancient city of Kaulon ten miles away.

DAY IV: PUGLIA

San Pietro

Skip the social media hotspots of Alberello, Ostuni and Lecce. The best of Puglia lies off the Instagram-map at places like Vieste, Monopoli and most importantly, tucked away in its heel, the Byzantine stronghold of Otranto. The city’s cathedral contains the skulls and bones of the 800 fifteenth-century martyrs who were killed by Turks for refusing to convert to Islam in 1480 (Turkish cannonballs are still found on the streets); its columns are spolia from a Minervan temple; and its giant twelfth-century floor mosaic displays scenes from the Old Testament.

Despite this, even the bishop’s seat is upstaged by San Pietro, a humble Byzantine church that lacks documentary evidence i.e. history. Scholars, however, have examined its frescos and found the earliest date to the tenth century and the latest can be assigned to the sixteenth.

It’s then a 90-minute drive to Masseria Torre Coccaro, a fortified farmhouse (complete with a watchtower to fight off the Turks) set in olive groves set a little distance from the beach. If it’s free, select the Aranceto suite as it comes with a swimming pool shaded by orange trees and cave-like living-quarters (complete with a fireplace the size of a portcullis).

DAY V-VII: ROME

Rise at dawn, it’s a five-hour journey to the elder Rome (as opposed to Constantinople’s Nova Roma), which likes to think Roma est patria omnium (it is everybody’s fatherland). Few today realise that what we now consider “Byzantine” was once the universal idiom of the Church until the Renaissance, or that the Papacy was dominated by Byzantines from the mid-seventh to late eighth century. Half-heartedly abandoned, the drumbeat of Byzantium pulses in the city’s subconscious, studding claustrophobic courtyards and obscure alleyways, punctuating its silent spaces.

Drop the car at the Ludovisi parking lot – opposite Hotel Eden – at noon. If you’re quick, you can get to some of the Byzantine churches before apathetic priests start to take liberties with their siesta hours. Don’t forget that most of the apse mosaics can be lit up by coin-operated lights. Note well, too, that what follows isn’t just a rehash of the famous “Seven Pilgrim Churches” itinerary (which, itself, marks the end of a long process that can be traced back to seventh-century texts such as the Itinerarium Salisburgense), as several (such as Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, San Sebastiano fuori le mura and the new St Peter’s – the old basilica would have been a different story) contain little that’s Byzantine in nature.

Even the Byzantines got involved with (iconophile) florilegia such as the late ninth-century manuscript preserved in the Marciana Library (Marcianus Graecus 573 [fols. 2-26]), first published by A. Alexakis, 1996, which describes nine miraculous images from the East and Rome.

Furthermore, don’t let any jargon confuse you. The four “major” basilicas were formerly known as patriarchal ones. Very simply, the papacy assigned a church to each member of the Pentarchy – the five Christian leaders of the ex-and-still Roman oikoumene (inhabited world). The Lateran belonged to Rome, St Peter’s to Constantinople, St Paul’s (fuori le mura) to Alexandria and Mary (Maggiore) to Antioch. The fifth, St Lawrence (fuori le mura), which goes to Jerusalem, has rather oddly been relegated to a minor position.

It’s also worth noting that these don’t correspond to the conventional bishoprics of their regions but their “Latin patriarch” equivalents (thankfully, the Latin seat of Constantinople has been discontinued: a line of men that began rather ignobly with the wretched embezzler of Hagia Sophia’s riches, Tommaso Morosini, and ended in 1965).

After visiting the sites below you’ll have serious church fatigue. So collapse at the Hotel Eden. Once the haunt of figures like Hemmingway and Fellini, it’s wedged between Spanish Steps and Villa Borghese, and situated around the corner form Via Veneto.

I used to stay when it was admittedly a more understated animal. Nowadays it’s a slightly more Dubai-esque creature with bling marble and gold bathrooms and a Fabio Ciervo restaurant with panoramic views over Rome that’s priced at roughly £200 per head. The good news is, first, almost all the staff have remained from before the revamp. Second, during its 18-month renovation, rooms were cut from 121 to 98 so suites have ballooned in size. Bright, airy, neutral and tall, ours is faultless from its view overlooking Villa Medici to its Vispring beds, mahogany furniture and Rubelli curtains.

Santa Pudenziana

Home to the oldest extant Byzantine mosaics – unusual for their blueish-silver background in contrast to the usual tarnished-coin hue – in Rome, Santa Pudenziana not only boasts tesserae that date to the fourth century but also has a claim to being the oldest place of continual Christian worship in the city. Dedicated to the daughter of St Pudens, St Peter’s first baptism in Rome, the basilica now sits roughly 12 feet below the current street-level and so can only be accessed via a staircase.

Santa Pressede

Built by Pope Hadrian I in the eighth-century but placed at the centre of Paschal’s mission to translate the bones of Rome’s martyrs to a few restricted locations, Santa Pressede’s mosaics are some of the world’s finest. Dedicated to the sister of Pudenziana (see above), Pope Paschal can be spotted with his mother, Theodora (look for the square halo – a sign that someone holy is still alive). Only the chapel of Sant Zeno (complete with [one of many] column[s] of the flagellation) upstages its mosaic cycle. Though some claim Byzantine mosaics are inert, callous, static and stale, the reality is that their heavy-lidded lethargy is supposed represent the arrival of a new power, a redeemed nature. The woes of the past are attenuated and love nestles easily on the rescued soul.

Santa Cecilia in Trastevere

Believed to have been built on the home of the third-century martyr Cecilia shortly after her death, Santa Cecilia’s apse is often unfairly ignored as a distant copy of the one at Santi Cosma e Damiano and so barely studied at all. The inscription beneath is rather poetic: “Rutilat Hic Flore Iuventus Quae Pridem in Cryptis/ Pausabant Membra Beata Roma Resultat Ovans Semper/ Ornata Per Aevum” or “Youth glows red in its bloom, limbs that rested before in crypts: Rome is jubilant, triumphant always, adorned forever.”

Santa Maria Maggiore

Standing on the Esquiline hill and possessing the tallest bell tower in Rome, Maggiore has had many names throughout history. Perhaps its most renowned was Santa Maria della Neve (St Mary of the Snow) after its plan was miraculously outlined by snowfall in the mid fourth-century. Its most famous possession (greater even than its fifth-century nave mosaics and triumphal arch or thirteenth-century apse, which contains a style of mosaic similar to the basilica of Sant’ Ambrogio, Milan) is a Byzantine icon known as Salus Populi Romani, AKA Regina Caeli, which Gregory the Great welcomed from Crete in AD 590.

Santa Maria Domnica alla Navicella

Another of Paschal I’s creations, it was founded in late antiquity on the ruins of the barracks of the fifth cohort of the Vigiles. Outside, the Roman stone boat (turned into a fountain by Leo X) was probably a votive offering from the Castra Peregrina (Camp of the Strangers) – a military camp across the street. Inside, Byzantine craftsmen have created another gorgeous apse (yes, there’s Paschal in his square halo of the living again), with a triumphal arch held aloft by porphyry columns below a coffered wooden ceiling added by Ferdinando de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany.

Santo Stefano Rotondo

Located opposite Navicella, on the crest of the Celian hill, sadly the three arms of fifth-century Santo Stefano were pulled down in 1450. What remains is rare in type. Indeed, you’d have to cast your eyes east, towards the martyrea of the Byzantines, to glimpse its parallels. Originally three concentric circles (at 22, 42 and 66 metres in diameter) intersected by the four arms of the cross, the two inner rings of arcaded colonnades still stand, though much of the church has not been so lucky. Struck by an earthquake in AD 847 and then sacked by the Normans in 1084, rich mosaic and marbles have long disappeared leaving only a lonely the apse mosaic in the chapel of Sts Primus and Felician, which shows each saint wearing a tablion next to the cross.

Santa Maria in Trastevere

Founded by Julius I in the fourth-century and rebuilt by Innocent II in the twelfth, if you’re wondering where the Baths of Caracalla went look no further than the nave colonnades of Maria in Trastevere topped with ionic capitals. Suffused with half-sighed prayers, an unearthly grace and the naked glitter of mosaics, many come to see Cavallini’s Annunciation and the sixth-century Maria Regina icon in the Altemps chapel. The latter, produced using the encaustic technique, shows the Theotokos as an empress in a dark purple dalmatic, lavish maniakion (neck-collar), scarlet buskins, pearl prependoulia (of the stephanos type equal in rank to the emperor’s stemma), and was once displayed holding a precious metal cross (later removed and painted instead).

The earliest known fully-fledged representation of Maria Regina that survives today is a mural on the palimpsest wall of the Santa Maria Antiqua church in the Roman Forum. The elevation of biblical figures to the purple was not unique to Mary. To take one apt example (as Mary was of the house of David), the sixth-century mosaic medallion at St Catherine’s on Mt Sinai portrays David as a Byzantine Emperor. Even non-royal saints were converted, however, into the royalty of heaven – St Agnes for instance in the seventh-century apse of Sant’ Agnese church. Though Mary’s position was unique in that she may have been one of the few representations of the ecclesia in iconography, a theory advanced by Maria Lidova in her monograph on the Icon of Santa Maria in Trastevere, IKON 9 (2016), pp. 109-128.

Santa Maria in Cosmedin

Rebuilt by Hadrian I in the eighth century, Maria in Cosmedin is famous for being given to Byzantine refugees fleeing persecution by the iconoclasts. Indeed, its name comes from the Greek for ornament. Cosmedin’s frescos date a little later to Nicholas I’s reign (in the ninth century) and its main relic consists of the skull and bones of St Valentine, exhibited to the public on his feast day. Those hungry for more signs of Byzantium should make a beeline for the sacristy where there’s a fragment of a Byzantine mosaic that was originally part of a great mosaic commissioned by John VII for the Oratory of the Virgin at the old St Peter’s basilica.

Santi Cosma and Damiano

The oldest church in the imperial forum, Cosma e Damiano was an apsed hall (once attached to the third-century BC temple of Jupiter Stator) in the forum of peace before being converted by Felix IV in the early sixth century. Dedicated to the Byzantine martyrs, Cosmas and Damian, both twins and physicians and more importantly the superstar saints of the Mediterranean, its apse depicts the Parousia (second coming) with Christ arriving “on the clouds of Heaven with power and great glory” (Matt 24:30).

San Clemente al Laterano

Standing in a long valley that extends eastwards from the Colosseum, rising as it approaches Saint John Lateran, the original San Clemente was where St Jerome spoke and the relics of St Clement of Rome were brought by Sts Cyril and Methodios. Most of the church’s interior today dates to the twelfth after suffering greatly in the Norman sack of Rome in 1084. Its apse mosaic is a burnished gold and shows the Cross as the Tree of Life.

Santa Sabina all’Aventino

Rising above the orange groves of the Aventine, Santa Sabina was founded in the early fifth century by a presbyter, Peter of Illyria, using proconnesian marble columns that once supported a temple of Juno on the site. It would originally have been covered with the sort of mosaics that can still be seen at Ravenna but most are lost. Indeed, thanks to a botched baroque “restoration” job by Domenico Fontana, there are few highlights other than the fifth-century cypress door (complete with the pharaoh’s face re-carved to look like Napoleon). Instead, all that’s left is an ex-Byzantine structure missing its apse mosaic, ambo and iconostasis. Yet, for all that, the stones feel old. They echo ancient bursts of hope and sorrow; the pleas of a humanity broken like the reed.

San Giovanni in Fonte

Built by Constantine the Great in AD 315, San Giovanni in Fonte is the oldest baptistery in Christendom (its competition, the similarly named San Giovanni in Fonte of Santa Restituta, Naples, can probably be placed a little later) and provided a model for almost all later versions. As with Santa Sabina, major “restoration” work in the baroque period means that the ambulatory mosaics are long gone, though at least here there’s an antique green basalt font (the original was porphyry with a thirty-pound golden lamb and seven eighty-pound silver deer), and gorgeous chapels (dedicated to John the Baptist, John the Evangelist and the seventh-century St Venantius), of which the last is the finest.

San Giovanni in Laterano

First of the four major basilicas in Rome, San Giovanni in Laterano was once a palace before becoming barracks to an imperial cavalry squadron that picked the wrong side at Milvian Bridge (AD 312). The Roman church gathered there to condemn Donatism a year later and dedicated the church in AD 318. Since then it’s been sacked, burned and shaken by earthquakes so that most of what can be seen today dates to the reign of Urban V. Highlights include central bronze doors taken from the city’s Senate House, a statue of Constantine from the Baths of Diocletian, the cosmatesque pavement, and its apse (the higher part of which, with Christ and angels within river, dates to the fourth century).

N. B. Visit the Vatican Museum to see the stercoraria, red-marble throne, so named after the anthem sung at the papal enthronement: “De Stercore erigens pauperem” (lifting up the poor out of the dunghill, Ps 112).

San Paolo Fuori le Mura

Occupying the site of St Paul’s shrine since the first century, the fourth-century church remained almost completely intact until torched by a fire in 1823. Possessing a fine set of walls, built to keep Saracens out, the only survivors from the horrific conflagration include its fifth-century triumphal arch (themed around the apocalypse), thirteenth-century apse mosaic (displaying Christ seated between the liquid-eyed Apostles) and chains believed to have imprisoned St Paul before his execution.

Lorenzo fuori le mura

A papal basilica, Lorenzo’s is dedicated to one of the first seven deacons of Rome martyred in the mid-third century. Famous for giving pagan persecutors the old and poor when asked to hand over the Church’s “treasures,” he was roasted on a grid-iron for his troubles. Later the centre of funerary rites that focused on local catacombs, today its main Byzantine features include a triumphal arch, a narthex that contains several early Christian sarcophagi and a marble ambo decorated with green-marble and porphyry discs – as well as St Lawrence’s tomb.

Sant’Agnese fuori le mura

Built over the catacombs of Saint Agnes on a site sloping down from the Via Nomentana, the current basilica dates to the reign of Honorius in the mid-seventh century. Thankfully, the apse mosaic of an almond-eyed Agnes dressed as a Byzantine empress and receiving the crown of martyrdom survives (the frescoes above the nave arcades and triumphal arches date to the nineteenth century) from the same reign, flanked by Honorius and another pope.

The incantatory epigraph beneath reads: “Aurea concisis surgit pictura metallis… Vel qualem inter sidera, lucem proferet Irim, purpureusque pavo ipse colore nitens. Qui potuit noctis vel lucis reddere finem, martyrum e bustis hinc reppulit ille Chaos… (“Golden pictures rise out of beaten metals… And the rainbow among the stars produces such a light, and the purple peacock shines with this colour. He who can give an end to nights or lights, from here has repulsed Chaos from the tombs of the martyrs…”).

Santi Apostoli & Bessarion’s Villa

Santi Apostoli (Holy Apostles) does not look particularly promising from the outside. An early 18th century creature, only its crypt and bas-reliefs hint at older foundations. Possessing several chapels, Bessarion’s is perhaps the most beautiful, yet it was also forgotten for centuries until rediscovered by the architect Clemente Busiri Vici in 1959. Having died in Ravenna, he was transferred to the church in early December, 1472, where Sixtus IV presided over the obsequies. The Byzantine’s rather dry epitaph in Latin is followed by a no less austere distique in Greek that reads “Bessarion’s body lies here but his spirit has departed to God immortal.” If you’d prefer something a little less morbid, head to Bessarion’s villa on the Via Porta San Sebastiano.

The poet, Leonardo Montagna, wrote something a little more stirring on the death of Bessarion:“Nil tandem superest nobis de gente Pelasga/ Cum mors abstulerit Bessariona patrem./ Huic dum vita fuit, tibi adhuc sperare licebat:/ Nunc spes, infelix Graecia, nulla tibi est.” (Nothing of the Pelasgian people is left since death took Father Bessarion. As long as he was alive, there was still hope for you. But now, unhappy Greece, no hope remains.”

Santa Constanza

Perhaps the only fourth-century building in Rome that remains fundamentally untouched, Santa Constanza is worth visiting for two features alone: the mosaics that cover its barrel-vaulted ambulatory, as well as its apse mosaics. Built originally for Constanza’s sister Helena, nevertheless it was the former’s name that stuck. Constituting a fascinating mix of pagan and Christian symbolism, with religious iconography in its youth the church cum mausoleum reflects the ambivalence of its times – not least the fact Helena’s husband was none other than Julian the Apostate.

DAY VIII: FIESOLE

It’s a three-hour drive north to Fiesole. Stop off at Siena, half-an-hour south of Florence, if you fancy a break. There’s nothing particularly Byzantine but few are disappointed by its Italian gothic cathedral, which plays with black and white marbles (the colours of its civic coat of arms and the horses of its two founders, Senius and Aschius) in a manner found almost nowhere.

Fiesole is glorious – even Proust said so in A La Recherche du Temps Perdu. Founded by Etruscans, it once competed with Florence as a city-state in its own right until subjugated by its neighbour and reduced to the status of a Cornish village i.e. replete with the second homes of wealthy metropolitans who desired to live out the good life in a bucolic backwater.

More of a town-terrace to Florence than a city these days, Fiesole’s square (Piazza Mino da Fiesole) is lined with cafés, restaurants and tiny shops, and sits behind a remarkably well conserved Roman theatre. Not much is Byzantine, however. The closest is perhaps the tenth-century church, Santa Maria Primerana, but little dates to the period.

With nothing Byzantine around you have the perfect excuse to lounge about at Il Salviatino. A fifteenth-century palazzo that possesses more frescoes than the local museums put together, it also features a wood-panelled library, vaulted entrance hall and a terrace that simply has the best views of Florence’s red roofs filthy lucre can buy. Indeed, Salviatino attracts A-listers every year, to name-dropp just one: Michael Fassbender. No doubt they love its chic spa, secret passageways, antique baths (perhaps the weirdest soak I’ve ever had was in a sarcophagus here), marble fireplaces, TV-sets in giant mirrors and wash-basins set in formidable aediculae.

The only set-back for such an incredible property – with its twelve acre grounds shaded by lemon trees – is that the small pool feels like an after-thought. Shunted to the lavender-fringed flank of the hill, it’s a surprising omission given Villa San Michele’s oasis at the top of its property. Though the latter lacks a spa so perhaps it’s a mutual knock-out by the two heavyweights.

Day IX: Florence

The drive into Florence’s centre takes ten minutes. Parking is a nightmare, however, so if you’re enthusiastic wake up early and occupy a spot in the outskirts otherwise you’ll be doomed to splash the cash at the train station’s car park, which refuses to charge a day rate.

Baptistery of St John

Wander to the baptistery, which stands over an old Roman mosaic pavement and dates to the fourth century – the earliest historical report that points to it as an individual structure (set apart from the cathedral complex) traces it back to at least AD 897. Gradually overlaid with green Prato and white Carrara marble in the eleventh century, over time the baptistery lost its hemispherical apse in favour of a pavilion roof and gained the font of the city’s old cathedral, Santa Reparata. Highlights include Pisano’s bronze doors to the south, Ghiberti’s to the north, porphyry columns and, of course, the golden ceiling mosaics that feature scenes from the Last Judgment with Christ in Majesty.

San Miniato al Monte

You can’t get much more Byzantine than your city’s first martyr hailing from the heartlands of the Eastern Roman Empire. St Miniatus was a hermit who – radiating holiness – didn’t let the Decian persecution’s removal of his head stop him from taking it back, crossing the Arno and strolling back to his hermitage on the top of Mons Fiorentinus. His shrine later morphed into an eleventh-century basilica (with adjoining monastery), acquiring a choir raised above a large crypt, a splendid Romanesque pulpit and a thirteenth-century golden apse displaying Christ in benediction between the Virgin, St Miniatus, and symbols of the Evangelists with kneeling donor.

You’re then a fifteen-minute stroll from the Hotel Savoy, which, adjacent to the Piazza della Repubblica, couldn’t be more central if it pirouetted on the Duomo’s head. Like Hotel Eden, it’s recently been revamped but it’s still the grand dame of Florentine hotels. Our suite has a large living room, bedroom, dressing room and bathroom complete with mini-library, coffee-machine and dining table, all daubed in Farrow & Ball and decorated with furniture by local craftsmen.

There are a few potential slip-ups. The lack of a proper communal space, for instance, as well as a spa. That said, service is above and beyond, the bistro (complete with terrace) is the perfect mix of formality and breezy camaraderie, and – barring the nearby Hotel Brunelleschi, which is based in a restored Byzantine tower – there are few places this central that are so unabashedly historical and luxurious.

DAY X-XI: RAVENNA

It’s a two-hour drive to Emilia Romagna’s shiniest button: Ravenna. Lying on a low-lying plain near the confluence of the Ronco and Montone rivers, just six miles inland from the Adriatic, Ravenna is one of those cities that (like Amalfi and Venice) has forever looked East. Blooming with mosaics enshrined on the UNESCO world heritage list, the city was once the capital of the Ostrogothic kingdom, as well as the last formal outpost of Byzantium in northern Italy (its exarchate was lost to the Lombards in AD 751, Franks in 754 and gifted to the papacy in 757).

In many ways Ravenna is to Rome what Winchester to London, with Milan playing the role of York. A smaller satellite-capital, its historical genealogy ranging from Honorius to the Florentine Dante who died here in exile (his tomb is a ten-minute walk from Galla Placidia’s mausoleum) acts like a planet that can’t quite decide which sun it wants to orbit: the old or new Rome?

Be warned: despite its impressive number of historical curiosities, Ravenna is quite small, possesses a disproportionate amount of migrants (trying to charge for finding parking spaces) and very few quality hotels so, if you can, try to fit most of the following sites into one day and get a late-night flight from the foodie’s paradise, Bologna.

San Vitale

Almost entirely funded by Julianus Argentarius, the octagonal San Vitale was founded over a decade before the Byzantines took Ravenna in AD 540. Miss its cupola, which is full of dull eighteenth-century murals and head straight for the green and gold mosaics of the sanctuary and apse. Walk past St Andrew with his white afro into scenes of eucharists, angels and holy cities.

Keep going until you’re before a youthful, clean-shaven Christ the Redeemer (this is a theme in Ravenna – as well as Rome’s catacombs – the Archbishop’s chapel has a beardless Christ as emperor, too) sitting on the world, flanked by Saint Vitale (who’s being handed the martyr’s crown), two angels and Bishop Ecclesius. One of the few churches that’s more famous for its side-walls than its apse, San Vitale’s figures of Justinian and Theodora grace countless books on Byzantium and, here, stand with their respective courts emblazoned with Christ’s monogram, the Chi-Rho.

Mausoleo di Galla Placidia

Next door is yet another misnamed mausoleum (see Rome’s Constanza) as Galla Placidia died in Rome and was laid to rest in one of St Peters’ imperial mausolea. More likely an oratory commissioned by the empress rather than a mausoleum, it was originally connected to the narthex of the neighbouring Santa Croce. Shaped like a Greek cross, it’s slowly subsiding – in fact, it’s sunk almost five metres since the early fifth century. Filled with over 800 stars, the most important mosaics include Christ as the Good Shepherd, St Lawrence (with his flaming grate) and the apostles looking to heaven. Few visitors would want to leave without seeing the marble sarcophagi – though, in reality, they were likely the last stations for sixth-century nobles rather than the fifth-century emperors with which they’re traditionally associated.

Baptistery of Neon

A ten-minute walk south of the mausoleum, Neon’s baptistery is traditionally known as the Orthodox baptistery to distinguish it from its Arian counterpart, which at least still has its (rebuilt) church, Santo Spirito. Once a Roman bath-house, most visit to see the baptism of Christ in the medallion of its cupola. Sadly, however, several parts have been subject to eighteenth and nineteenth century restoration. In fact, the dish St John uses is the artistic license of Felice Kibel who clearly couldn’t resist overreaching his commission. Despite this, there are few more wondrous workings of colour than at Neon. Neither sickly tropical nor dully brown, they seem to stand for the sunlit uplands of the Kingdom of God.

Arian Baptistery

Once Theoderic’s Arian answer to the Orthodox Neon, Justinian had it converted into the church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin after taking Ravenna in AD 540. The cupola’s image is slightly simpler than Neon’s and shows the Holy Spirit descending on a young Christ flanked by John the Baptist and a personification of the River Jordan. A crowd favourite remains the Hetoimasia, an empty throne with cushion and crux gemmata that signifies that the Church is ever-ready for Christ’s Second Coming.

Archiespiscopal Chapel

Erected by a bishop named Peter II (when Arianism was the courtly religion), the Chapel of Sant’Andrea is the only chapel of the early Christian era to have survived intact. Its angels reaching out to the Chi-Rho are reminiscent of Zeno’s Chapel in Rome and the royal blues conjure a similar hue to Sicily’s Martorana. But the most celebrated mosaic, in a lunette above the exit, has few parallels – though he is slightly reminiscent of a weedier Colossus of Barletta. Showing a young, beardless Christ dressed as a victorious military emperor that treads the beasts (Ps 91), he has one hand placed beneath his chlamys and another holding an open gospel (reading “ego sum via veritas et vita” or I am the way, the truth and the life), as well as a red cross over his shoulder. All of which is meant to impress upon its audience that the orthodox faith is invincible, especially when compared to feeble, fallible Arianism.

Sant’Apollinaire Nuovo

A ten-minute stroll east, past Dante’s Tomb, brings you to Sant’Apollinaire Nuovo. Like the Arian Baptistery, it was (again) built as an Arian foundation but converted to an orthodox equivalent dedicated to St Martin not long after the Byzantines reconquered the city in the mid-sixth century. It’s “nuovo” only in the sense that the label once distinguished it from another church (long since gone) with the same name and, like so many others on this trip, suffered a barbarous baroque “renovation” that removed many of the mosaics. Fortunately, it still possesses 24 marble columns from Constantinople – decorated with Greek monograms on the capitals – and mosaics all over the nave and clerestory, the most important of which frame the palace of Theoderic and the port of Classe.

Theoderic’s Mausoleum

A five-minute taxi-ride to Theoderic’s park brings visitors close to his double-storeyed mausoleum, which remained unfinished even after his daughter Amalasuntha’s reign in AD 534. Laid using huge limestone blocks without mortar, its shallow-dome roof weighs over 200 tonnes and is marked by the name of each apostle on protruding spurs. Inside, its upper storey is dominated by what looks like a porphyry bath-tub, which may have been Theoderic’s sarcophagus, though he didn’t remain here very long given Justinian issued an order that had him removed and his mausoleum turned into an oratory in AD 561 – with a square tower surmounting it that served as a lighthouse! Later partly submerged as a result of silting by the nearby river Badareno, it was not drained and excavated until the nineteenth century.

Sant’Apollinare in Classe

Built in the first half of the sixth-century and located roughly five miles outside central Ravenna, Classe’s three aisles (divided by 24 Byzantine columns) were once covered with geometric mosaics, only fragments of which survive. Its side walls, too, were once smothered in rich marbles and later pillaged in the fifteenth-century for reuse in Rimini. Thankfully, the apse and triumphal arch still stand, and evoke a verdant garden whose light less reflects the light of the sun than emanates its own.

Above all, a star-speckled cross looms across the orb of a frosted lamp, somehow distant and mysterious yet also comforting and familiar. Instead of a sky, the gaze dissolves into the quivering gold of God’s vision and tourists soon realise they are entering the rapture: the Transfiguration of Christ, an intimation of the Second Coming.